“Unlimited class,” said Tom, bobbing back and forth in the seat behind me. “Unlimited class,” he went on. He was so very stoned. I was. too, but not like him, I was incapable these days of reaching such an oblivion. I needed to take a tolerance break.

“Shut up,” I said, and turned the radio up: police blockade on Eagle Rock Boulevard, it said. Vic, in the passenger’s next to me, said, “Isn’t that where we are?”

“Sure is,” I said, and peeled off into the closest lot, along with dozens of other cars, blurs of crimson brake lights folding into one another in the night before extinguishing themselves en masse, like a smothered bonfire. “We’ll wait it out here,” I said. “It’s a sweep — if we go backwards now, even if we stick to side streets, they’ll pick us off, one by one. That’s what they’ve been doing lately, apparently.” Vic shrugged, turned his head and body toward my illegally tinted window, and fell asleep. He could do that anywhere, his was a talent of some renown.

“If we’re not driving, we’re safe,” I said, to no one in particular, given the states of my friends: Vic snored discordantly, as Tom went on, “Unlimited class, unlimited class.” I turned the radio up even higher.

Then I turned it down again. “Dix, Thomas,” I said, the French way, like the Thomas in Thomas Bangalter — we’d taken four years of French together at Consuela High down at the beach. Tom was the only one of us three who ever approached fluency. We were far from the beach now, anyway.

“WHAT,” he said.

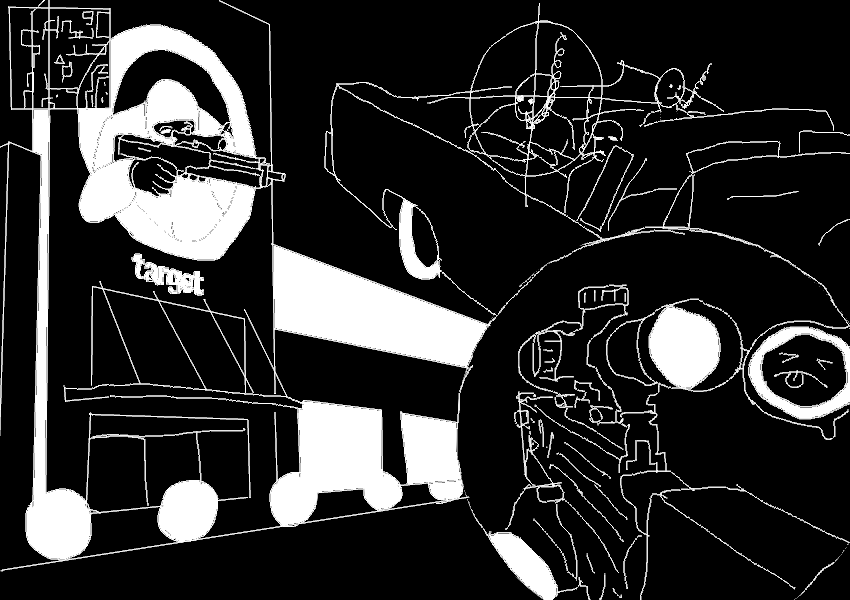

“Does this Target have a rep?” I asked — for that’s where we were, in the Target parking lot at Eagle Rock and Ave. 42, beneath the blaze of the all-seeing scarlet bullseye, lit up in florescence in the wet of the night.

“The other Eagle Rock Tarjhey does. Haven’t heard anything about this one.”

“And what’s the rep of the other Eagle Rock Tarjhey?”

“Let’s just say, I’d rather take my chances with the barricade than end up there.” He lit up a joint. I didn’t know he had another.

“Gimme that,” I said, and he did.

The stench woke Vic up. “Gimme that,” he said, and I did.

Target stores everywhere across America were harassing stoners, losers, and layabouts. First, they chased us out with sticks and brooms. Then they got serious, started lacing the Doritos, the Haribo products, and so many other smoker stalwarts, with PCP, with fentanyl, with rat poison, even. Now, in certain jurisdictions — far from Southern California, mind you (well, not too far, Arizona being a mere fevered night’s drive away) — Target employees could shoot at any suspected pothead or drug user. Bloodshot eyes alone gave them proper corporate cause.

“I think we should stay in here,” Tom said, upon the rotation’s return to him.

“You were thinking of going in?” Vic asked.

“Well…” I trailed off. Thing was, I needed food for my dog Randy and a gift for my little niece Risa, some Star Wars LEGO for her birthday party at the Islands restaurant in Glendale in only two days. I was running out of time. “Just what were they doing in the other Eagle Rock Target? What’d you hear?”

“Gimme that back,” Tom said to Vic, reversing the rotation. He obliged this request with no complaint, as we knew how trying information, and its revealing, could be for Tom, who killed the joint and cleared his throat. “You remember Otis?”

“Football player?” Vic said.

“No, that was Otay. Otis played the viola. He was first-chair at the viola.”

“In which orchestra?”

“Fucking Christ, Veek, I don’t know which orchestra. One of them. Did you know him, Zeke?”

I scratched my head, I actually scratched my head. “Rings a bell,” I said. “Hairy guy?

“Covered in it,” said Tom.

“He wear a hat?” I asked, shooting in the dark.

“One of those colorful ones with the little spinner on top, as I recall. What do you call that?”

“Propeller hat,” said Vic.

“I don’t think it’s called that,” replied Tom.

“No, it definitely is,” said Vic.

“Regardless, that’s what he wore. Started as some orchestral hazing and then it stuck, I guess. It offered him a sort of actualization. Do you remember him, Zeke?”

“I do,” I lied.

“I remember him,” Vic said. He was probably lying, too, our memories were shit now. Tom’s wasn’t, though — he was smarter than us, by day he worked as a mechanical engineer for various defense contractors on the Westside and down in the South Bay, our old stomping grounds.

“It’s definitely called a propeller hat,” Vic said.

“Regardless,” said Tom, “did you hear what he got up to after school?”

“I didn’t,” I said, and Vic shook his head, too.

“He dropped out of SLO. Agriculture major. Took some chemistry grad student from UCSB with him, they started a Delta 8 extraction operation in a warehouse in Moorpark. So he was plugged in. Kid smoked a lot of weed, is what I’m saying. Gave up the viola for the weed. Something happened to him that summer, before he started up at SLO. And it’s a Cal Poly, you know, a technical college, so you change your major there, you have to do all this extra shit, like, apply into a different school. Like, he had to apply in as whatever it was he was going to do at first. Can’t remember what it was now, art history or something. Can’t remember now.” He tripped up for a moment. Information could truly be burden to Tom. “Something happened that summer and he switched into the agricultural school, and it required this rigamarole. He basically had to do all these science GE’s to even just switch and it would take him an extra year to finish the degree, too, or something. But it didn’t matter, anyway, because he didn’t finish, and he made a lot of money, actually, from what I hear, and now he’s dead.”

“He’s dead?” Vic said.

“What’s that got to do with Target?” I asked, eyes, as always, on the prize.

“That’s where he died. Target. The Eagle Rock Target. Not this one, the other one. The one off Colorado. The one by the Seafood City.”

“I’ve been in that Seafood City,” I said. “Not the Target, though.”

“It’s good you didn’t,” said Tom, “because then you’d probably be dead, too. Knowing you.”

He filled us in: “Otis was blowing clouds everywhere he went. Everywhere. Because he was a dorky little vape-juice kingpin, when it came down to it. So, he blew clouds, as was his prerogative, really his God-given right. But I guess that life took him into some pretty offline circles. By which I mean: dude vaped in the wrong Target. Didn’t know any better. They found his body — in pieces — locked behind those glass video game cases. I’m saying: severed limbs stuffed beneath the Switch games.”

“Christ,” said Vic, and he lit another joint. (These people were holding out on me.)

“Gimme that,” I said. Greedily, I smoked it down as fast I could.

“Come on, dude,” said Vic.

“Man, come on,” said Tom.

I apologized to them both; they forgave me instantaneously, such was our addled state and genuine reverence for one another.

Finally, I was thinking straight. “There a Walmart around here?” I said.

“Yeah, let’s go to Walmart,” said Vic.

“This time of night, Burbank one’s probably the closest one open.”

“Fuck that,” I said, and on my phone Googled “walmart eagle rock,” and cursed again when the suggested result was the Target off Colorado.

“Didn’t you say something about not driving?” said Vic.

“Let’s just kick back here for a minute,” Tom said. “You got satellite radio. I got a few more joints.”

“Same here,” said Vic.

“So you are holding out on me!” I said, much too animatedly for my own good.

“Dude, it’s not like it’s blow,” said Tom.

“You can get weed from any store in the world,” said Vic.

But I couldn’t let it go. “You’re holding out on me!” I said again, boring even myself.

“Dude,” said Tom.

“Dude!” said Vic.

“Veek. Thomas,” I said. “Relax.”

“We are relaxed. Aren’t you the one? The one confronting us?” Vic said.

He had a point. “I’m hungry,” I said. “You goons got anything to eat?”

“Spam sandwich in my backpack,” said Tom.

“Eww. No thanks.”

“Don’t worry,” he said. “It’s not for you. Like. You can’t have it. It’s mine.”

“I’ve got nothing,” said Vic. “We could order Domino’s.”

“To a parked car?”

“Sure, the Tracker’s got a little notes section you fill in. We’ll put in the plate number, they’ll find us.”

“I’m gonna pass,” I said.

“I don’t need Domino’s, I got a Spam sandwich,” Tom said.

“Let’s just go inside,” I said. “They got Starbucks. At least the sign alleges as much. I’ll buy you both cake pops.”

“I could go for a cake pop,” said Vic.

“They sit out for days,” said Tom.

“You should buy me a cake pop, Thomas, with all that blood money you’ve been making,” said Vic.

“It isn’t blood money,” he flatly replied. “I don’t appreciate that kind of talk. I work on telecommunications satellites. For civilian application.”

“Don’t take his blood money, Veek,” I said. “You’ll taste it in the pop. Take my hard-earned honest dollars. Take my beautiful fiat. Take my two-ninety-five.”

“It’s all awfully tempting,” said Vic.

An immense odor suddenly violated my car’s interior, an eternity-piercing meat-smell, the stench of ham-corpse, the nose of pungent preservative. And there was Tom, there in the backseat, eating his canned pork sandwich, and between bites grinning the grin of a young man paid to build machines of death, and paid generously for that task.

I didn’t hold too much against Spam-enjoyers, but knew for a fact that bag had been on Tom’s person for at least a week and half. I had to get out of there. I opened the window and shoved my torso outside into the damp, dark night, like a parched traveler overcome at an oasis. But it wasn’t enough, the Spam smell lingered in the air. I had to seal Tom away. I dragged myself back inside, holding my breath as I bit my tongue. I rolled the window back up, untwisted the key out from the ignition, and fled the car. Vic did the same just a half-second later.

“Did you recover precious cargo?” I asked. Across the roof of my car, he held out to me a Ziploc sandwich bag stuffed with his fastidious joints. “You’ve earned your cake pop, my good man. Two or three, even.”

“This is my entire stash right now. Here, in my hands. Here it is.”

“Sparing it the stench, Veek?” The cool night woke me up a bit, it made me want to carry on, to thrive.

“Something like that,” he said. He sat down on the hood of my car and lit one. I joined him. The hood was sturdy enough for us both. Other pairs all across the lot did exactly the same, smoking whatever plant matter they found mashed into car floor-mats, lounging in the safe of the dark.

I weaved through red cement spheres, dragging Vic through the automatic sliding doors—“They need to wash their windows, man,” he said as I did.

I saw what he meant: the glass of the doors and the windows beside them were stained in streaks of a translucent reddish-rust hue, still very possible to see through but obfuscated noticeably, like someone hastily erased a holiday acrylic display from them, although I couldn’t recall any Target store painting pastel-colored Easter eggs or neon-green Christmas trees onto their exits and entrances, perhaps in the 90’s, but certainly not anymore.

If anything, the whole enterprise held a sickly technocratic sheen these days, this particular storefront’s matte siding resembling materials which might line the sci-fi structures at the EPCOT Center—but cast in red, of course.

I scrambled through sharp LED light to acquire a red plastic shopping cart. Were he smaller, surely Vic would ride inside it as I pushed him along through the store; instead, he walked close behind.

“Do we really need a cart?” he asked, as we passed through the kitchenware and the women’s clothes and into the bowels of the store: toys, electronics, seasonal fare (must be Valentine’s Day in here, I figured, and it was).

“To blend in,” I stage-whispered, pushing the cart along with what I hoped appeared as a faux-fatherly eagerness.

In the parking lot before we’d already prepared: we dropped Rohto Eye Drops into our eyes, which stung like you were sprinkling vodka into them instead; we sprayed ourselves down with Ozium Air Sanitizer, which sent our skin crawling as we hosed it all over our clothes, and surely catalyzed cancerous cells within our air canals.

Vic had left his stash back with Tom, after all, after we spritzed down my car’s interior with more of that carcinogen spray. Tom insisted he wouldn’t stink it up any further, beyond the always-foretold pot-smoke stench, if I let him remain in the car. I told him it was fine, but that I wouldn’t bring him anything back, on account of his “no risk” mindset. He said that that was fine, that he had everything he needed inside the car with him. I had no clue what he meant. I guess he meant weed.

“Do we really need to buy a LEGO set tonight?” said Vic now, as we set off down that aisle.

“I just like to look,” I replied, and grabbed the first medium-small Star Wars kit I could find, in this case Anakin’s Jedi Starfighter.

Vic sighed theatrically. “Let’s get back to the front,” he said, “I thought we were here for Starbucks.”

“We are! But I want to grab Randy some food, too.”

“Christ,” said Vic.

“Keep it down,” I said.

“Can I help you?” said a voice from behind us.

We turned around.

His name-tag read REESE. He was shorter than I was, shorter than Vic, too, Vic was three inches shorter than me and Reese was three inches shorter than Vic, by the look of it. He must have been 22, maybe even as young as 19. His blotchy skin was surprisingly tanned. He was sort of a twink, I supposed.

He spoke with the barest hint of a speech impediment overcome, far deeper than you’d expect from such a person. “Are you boys lost?” he said. Boys. It didn’t sound comradely. He talked like he was forty years older than he was.

His eyes were dilated, pupils big as pennies, you couldn’t make out what color they were beyond those black discs.

“Could you point us over to pet food?” I asked, earnest as I could muster.

“I’ll take you there,” he said with no emotion. “Follow me.” With that, he turned around and set off, and us behind he. We felt like we had no choice. Nick grabbed the cart from its side, too, and together we took up practically a whole aisle as we marched through the store. But most of the parking lot crowd had remained there, outside in the posse of folks who'd pulled over just as we had. It wasn’t a problem for Tom and me to take up so much space as we passed along the aisle set through the dead center of the store, past kids’ apparel and bedsheets. I didn’t realize until then just how widely known the Target stoner lore had become, how the store could remain so desolate with all those cars in the lot out there.

They were smart and we were dumb. I knew it as we glided through the empty store behind Reese, despite nothing truly unbecoming having yet occurred. Vic knew it then, too, I’m sure, but I never had the chance to confirm it with him.

Sure enough, Reese did get us to pet food. I stuffed a 25-pound bag of Natural Balance onto the cart’s lower rack and thanked him.

“It’s what I’m here for,” he replied.

Then he looked to Vic and said, for the first time without any apparent coldness, “What’s that you’ve got there?”

“Me?” Vic said, dumb or playing it.

“Yeah. Over your ear.”

How hadn’t I noticed? It was a joint from his stash, wedged between the twice-pierced cartilage of his upper ear and his neatly-kept sideburn. Did it register as a pen to me? Did he place it there during the walk from my car to the entrance, after I’d finished checking for exactly this sort of thing? Was it even there before this moment at all?

Two enormous men in plainclothes, one for each of us, grabbed Vic and me from behind, twisting our arms back as they shoved us toward the front of the store. I couldn’t figure how it happened so fast, the whole place must have been bugged. Reese hadn’t said anything so strange, nothing that stuck out to me as an obvious code. Maybe he made a certain physical gesture for cameras overhead, in their black-glass bubbles? Whatever it was, I’d missed it, and here they were, ready for us.

They dragged us through an empty cash register and past a great swinging steel door marked EMPLOYEES ONLY set between the drinking fountains and the brief hallway to the bathrooms. To my immense surprise, they pulled us down a palely-lit flight of stone stairs, in single file, so as to be in the order of: me, goon, Vic, goon. Reese hadn’t joined us, after all. There was no use struggling, the men kept telling us, firmly but softly, as we realized they held needles, syringes of something, to the tops of our spines.

They dumped us into a sort of concrete cell at least three or four stories underground, locking us behind another elephantine, shiny metal door. We heard their footsteps clanking as they departed for the surface. We heard them laugh.

Now I took in our surroundings. They weren’t so promising. Not even a vent visible down here. The floor, walls, and ceiling all took on the same hue, a silvery wash only differentiated by the steel door—which had been painted red on this side, because of course it had.

“Knock knock knock,” we heard someone say now, through the other side of it.

We said nothing in response.

The door swung open. The men in plainclothes, our abductors, had returned, after no time at all, accompanied by a man in a store uniform holding a clipboard in one hand and a plastic Target bag in the other, its contents unseeable to me. This new man’s name-tag read JOSIAH — MANAGER.

“Hello there,” he said. His voice was, again, much deeper than his appearance would suggest: he was our age, well-kempt, blonde, Vic’s height, give or take an inch, but he sounded like an aged James Coburn. “So, you’re my latest, eh?”

“These boys are smokers,” said one of the plainclothes men.

“We’re not,” said Vic. There was an unfamiliar flatness to his voice now. Was he resigned to whichever fate was likely on its way? He was white as a swan’s feather in the face, I saw.

“Queer little stoners,” said the other abductor.

Josiah the Manager set the bag down onto the cement floor and approached me. He looked into my eyes. His were blue. Then he smelled my neck. He took a step back and wrote notes on the clipboard. He held his hands up into a rectangle, peering through them like a cinematographer framing a shot, me as its foregrounded subject.

“He’ll do,” said Josiah the Manager. “Other one’s much too short,” he said, without even really looking over at Vic. “Do your thing,” he said, and the plainclothes men let him out through the red door before pulling it shut once more. (His steps back up to the store were too soft to hear.)

Another knock at the door: this was all happening so very fast. A meek-looking man in a red polo and many-pocketed cargo pants nodded hello at our abductors and left two red plastic garden chairs before heading back up.

One of our abductors took the chairs from their backs, dragging them, and pushed them up against the wall perpendicular to the red door. The other one started rummaging through the plastic bag the manager had left on the floor. Why hadn’t I thought to grab it? I turned out to be not much of anything in a situation as dire as this.

Vic looked to be faring even worse. We watched as the one bag-ruffling abductor tossed a roll of duct tape to the other at the red chairs. He went on to tape their legs to the ground, their backs to the wall. We were hypnotized by the sound of him unfurling the tape, tearing it off with his teeth.

“Bring him here,” he said when he was done. The bag-rummager grabbed Vic, pulled him across the room, and pushed him down into the chair closer to the door. The other began taping him in place.

“Stay on that side of the room,” said the one without the tape. “Come closer, he dies, you die.” He grabbed the bag from the middle of the room and returned to Vic in the chair. I must have been 10 or 12 feet away. The man dumped the contents of the bag on the floor before Vic. Boxes of Blu Ray’s and TV-on-DVD sets in plastic security cases cascaded out like hail crashing against the cement floor. I wasn’t able to make out many of the titles from my vantage, save for some Underworld sequels.

“No one can ever figure out how to open our security cases,” said the goon who’d done the taping, “or replicate the tool used to open them. People have done it at Best Buy, but not here, or at any other Target location in this great country. No one is devious enough, really, to figure out how to open these cases. So no one steals from our fine selection of films and television sets and we get to have a great time opening the cases for our customers down here.”

“Boss said he needs a 300 opened,” the other one said. He fished through his pile, pulled out a film. “You think he meant this?” holding up a copy of 300: Rise of an Empire.

“Is the first film in there?”

“Doesn’t seem like it.”

“Then that’s what he meant. Give it here.”

He tossed it to him. “Open your mouth,” said the one standing over Vic. “Smile with teeth.”

“Please do it,” I said to Vic between sobs.

“No talking!” said the bag-ruffler.

“Show me teeth,” said the other one.

Vic finally obliged him.

The man drove the corner of the security case into Vic’s teeth at full strength and speed.

Vic screamed, blood streamed from his mouth, some teeth, too.

The abductor gently pulled the film out from the plastic case — the smash seemed to have done the trick. “We’ve got Rise of the Empire!” he said.

“Actually,” stammered the other one, “I did find the first film in the pile.”

“Toss it here. That’s okay.”

Knowing what was coming made nothing easier for me. I can’t imagine how it felt for Vic. He had a sweet tooth. He had an extensive orthodontic history.

“Okay. 300. Show me that smile or I’ll slit your throat right now.” Vic did so. It was the strongest-willed I’d ever seen my friend become. The abductor slammed the case into his mouth again.

“What’s next?” Now vomit rolled down Vic’s chin, along with the gush of blood, the thickening stream of teeth. But he was mostly quiet now.

“You’re killing him!” I said.

“One more word out of you, I feed you your friend’s nose and ears,” said the bag-ruffler.

I shut up.

“What’s next?” said the other one.

“Hill Street Blues, complete series.” Christ. He fished out the largest set, contained in a security case the size of a small terrarium. “This’ll be good,” he said, as the other started humming the theme.

“Toss it here,” he said. He managed to catch it. Then he said to Vic, “Sorry, kid.”

He opened his face with it.

Vic was nothing now, just a torso, some arms, some legs.

I started gagging, then retching, then barfing.

“Puke all you want, kid,” said Vic’s executioner. “They’ll spray down the room when we’re done.”

“Yeah. Get it all out,” said the other, laughing a little, even.

So, that’s what I did, more or less, and that’s why you’re reading this now. Soon they’ll grind me up into a plate of glass, they’ve told me. All the windows at the new Target builds these days are made from folks like me, it turns out. Cuts down on costs, apparently. They patented a chemical process. Vic wouldn’t result in a whole pane, apparently, but I’m just tall enough to fit the bill. They’ll probably make me into a door, they told me.

They took me across state lines. In the back of an empty sixteen-wheeler. I must be in Minnesota now. That’s my best guess. I’ve befriended my jailor, although I’ve never seen his face. He feeds me only with Fruit by the Foot and Powerade. Red Fruit by the Foot, red Powerade.

He’s taken pity upon me, my jailor. Says most stoners are “the poorest of conversationalists.” But we’ve had much to talk about — music and art, the natural world. He’s an avid climber. He’s an avid whitewater rafter. He won’t tell me his name. Says that’s against protocol, says that would make everything so much harder.

He says he would spare me if he could, that it’s out of his hands. Says they’ll kill his whole family if anything goes awry. Three kids.

I said he had nothing to worry about. Said I’d be a model prisoner. And I am, except for this. My one request was he bring me a scroll and a pen. I gave him Tom’s dad’s address and he agreed to send what I’ve written here to him when I’m gone.

I write this late at night. My jailor told me when to do so, when the rest of the guards pay the least attention. But I haven’t seen a single other guard. He could be lying to me, for all I know. It could be just the two of us here, wherever we are.

Now I must address you directly, Tom. But words fail me. You were right, of course. You were right about everything. You always are. Vic died in pain. I couldn’t stop it. I wanted to. Actually, I didn’t want to. In that moment, I didn’t want anything. Everything was a blank, all a complete blur, as one might say. I’m amazed I’ve been able to write this account. It’s taken a week or so. I have to stop in the night when I hear an unfamiliar sound. And I hear such a sound now, so I better-